Revisiting Chalcedon

Unpacking the riches of ancient Christological debate for today’s church.

While it might seem archaic to quarrel over the identity of Jesus Christ, the progression of epistemological relativity has cultivated a deep demand for renewed biblical and theological precision concerning Jesus’s person and work. It would seem that the preponderance of theological education has done little to quell the feud over the nature and personhood of God’s Son, which has contributed to a dynamic of Christological confusion that filters across denominational lines and fosters a spirit of restlessness in the people of God. To illustrate this doctrinal malaise, we need only examine the findings of the most recent State of Theology survey, which canvasses U.S. adults from a wide range of ethnic, religious, and social backgrounds in order to evaluate the biblical and theological consciousness of the average American. In 2022, researchers found that 43% of respondents who identified themselves as “evangelical” agreed with the statement that “Jesus was a great teacher, but he was not God,” which was up from 30% just two years prior.

The fallacy of bifurcating Jesus’s identity is not a modern project, though. Rather, it is a descendant of the Christological discord that plagued the early church in the first few centuries of its existence. Accordingly, to neutralize this contemporary threat to Christology, the church is exhorted to retrieve and reaffirm the robust biblical and theological verdicts of Christianity’s historic faith, which cohere with the authoritative and definitive revelation of the person of Christ as found in God’s word. To that end, attention must be given to what might be deemed the climax of early Christology at the Council of Chalcedon, which, according to Justin S. Holcomb, furnished “the most significant Christological statement of the faith the church had yet produced.”1 Consequently, with a renewed grasp of the historical and theological repercussions of Chalcedon, believers will be equipped to not only declare and defend the scriptural definition of Christ’s person but also to savor Christ’s redemption, which is univocally tethered to the revelation of the embodied Son of God.

How Orthodoxy was Crafted

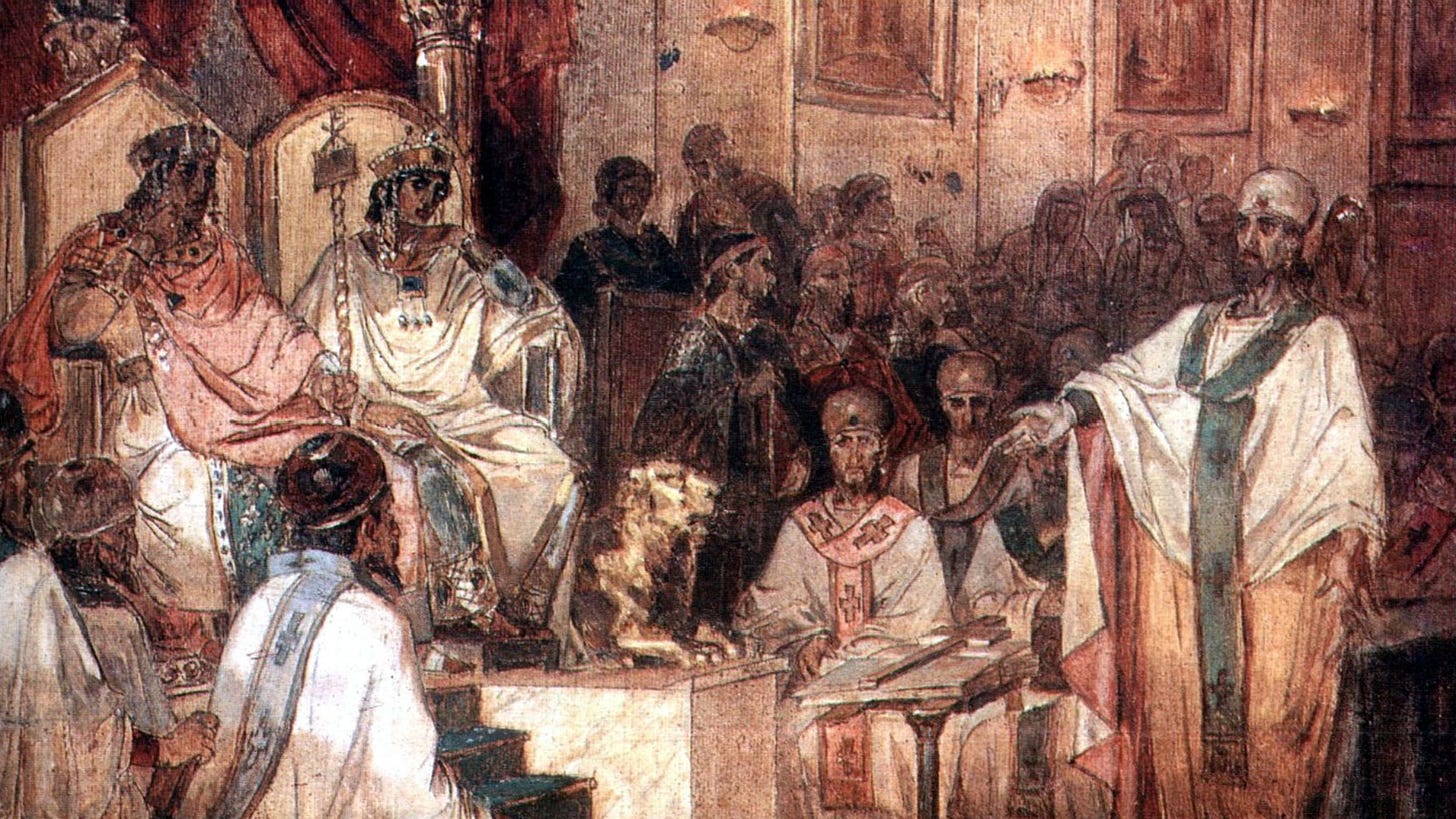

In 451, Marcian, the newly minted and betrothed emperor of Rome, summoned over six hundred pastors and theologians to the Council of Chalcedon, at which it was hoped a consolidated definition of Christ’s identity would be reached. Even though their bodies had already been buried by the time delegates convened, the rival Christologies of Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorius of Constantinople continued to echo through the halls of the church of St. Euphemia, which played host to the scores of bishops and emissaries who had descended upon Chalcedon to pilot the church of Christ into a more unified future. In the decades leading up to this conference, the church endured a series of theological skirmishes, the bulk of which concerned the personhood of the Son of God. The Christological schools of Alexandria and Antioch continued to foment debate and division even after the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381, respectively. Although those previous synods made great strides in articulating and affirming biblical Christology, extremists on both sides perpetuated the dissension, which reached a fever pitch when Nestorius became bishop of Constantinople in 428.

Nestorius was a firm proponent of acute Antiochene theology, which emphasized a distinction between Christ’s human and divine natures, effectively severing him into two persons. The bishop of Alexandria, Cyril, who had been appointed to office sixteen years earlier, voiced considerable concern over Nestorius’s segregated interpretation of the Christ of God. Much to the chagrin of Nestorius, Cyril vehemently maintained that the use of the title Theotokos, which is Greek for “Mother of God,” not only properly incorporated the Virgin Mary in the divine scheme of redemption but also highlighted the mystery of the incarnation of God’s Son in the person of Jesus. In the first of his tomes against Nestorius, Cyril attests that Mary “is [the] Mother of God, because the Only-Begotten has been made man as we, united of a truth to flesh, and enduring fleshly birth and not dishonouring the laws of our nature.”2 Accordingly, the merits of the designation Theotokos are neither esoteric nor abstract. They are consequential to orthodox Christianity since the identity of the one who accomplishes the redemption of humanity is at stake.

As the tension between Cyril and Nestorius continued to escalate, the Council of Ephesus was convened in 431, in hopes of settling the dispute. This hope was quickly dashed, however, as Nestorius’s advocate and delegate John of Antioch was delayed in coming to Ephesus, allowing Cyril to assume nearly unchecked control over the proceedings. As a result, the council affirmed Cyril’s Christological position and condemned Nestorius as a heretic. Despite the relative success of Ephesus for Cyril and Alexandrian theologians, the uneven representation tainted the process and only served to further the animus between the two sides. Nestorius would later bemoan the council’s prejudice by protesting: “Who was judge? Cyril. And who was the accuser? Cyril. Who was bishop of Rome? Cyril. Cyril was everything.”3

In response to the obvious bias of the decision at Ephesus, John of Antioch called for his own council, at which concessions were made to legitimize the use of Theotokos while also excommunicating Cyril. With both theological schools in a deadlock, Emperor Theodosius II intervened and coerced Cyril and John to endorse the Formula of Reunion in 433, which sought to coalesce the divergent Christological conclusions into one unifying vision. In so doing, the Formula of Reunion furrowed “Christological language that allowed Alexandrian and Antiochene models of Christology to be orthodox, while also rejecting the extremes of each model.”4 Although the two sides had seemingly come to a point of resolution, it was not without compromise, as John of Antioch was obliged to cosign the condemnation of Nestorius.

In the next decade, the church underwent a considerable season of transition. Along with the appointment of Leo the Great as the new pope in 440, Alexandria and Constantinople would both be under new bishoprics by 446. What’s more, with John of Antioch’s death in 441 and Cyril’s death in 444, the ecclesiological landscape underwent a seismic shift that was dominated by “new faces and new personalities,” which, as Hans Boersma notes, did little to erase the underlying conflict between the Alexandrian and Antiochene methods of Christology.5 Although much had changed, much had remained the same, as is evident in the ascension of Eutyches, a Constantinopolitan monk who rejected Cyril’s concessions to the Formula of Reunion. Eutyches’s Christology was thoroughly Alexandrian but taken to the extreme position known as Monophysitism, from the Greek term monophysis, which asserted that Christ possessed only one nature. In this paradigm, the incarnation of the Son of God constituted an event wherein Christ’s humanity was fully assimilated into his divinity, resulting in a single, univocal nature. Despite the Monophysite tendencies that were later attributed to him, Cyril’s Christology was derivative of Christ’s hypostasis, which affirmed Christ’s two natures in the one person of Jesus. Eutyches’s remix of this position reawakened the Christological controversy that had plagued the first half of the 5th century.

The burgeoning tensions were exacerbated by another Ephesian conference in 449, which legitimized Eutyches and condemned bishops Flavian of Constantinople, Theodoret of Cyrus, and Domnus of Antioch for their appeals to the Formula of Reunion. Much like its predecessor, the 449 conference was controversial due to its uneven representation and Monophysite prejudice, which Dioscorus of Alexandria, who presided over the meeting, unsurprisingly allowed to unfold since he was sympathetic to Eutyches’s Christological position. Accordingly, the “Robber Synod,” as it is commonly called, did little to bring about a unified explanation of Christ’s nature and person. The apparent success of extremist Alexandrian Christology was short-lived, however, as the sudden death of Emperor Theodosius II in 450 prompted his sister, Pulcheria, to formally reopen the matter.

After the matrimony of Pulcheria and Marcian, imperial influence aimed to subdue the belabored theological turmoil by calling for a new conference, the Council of Chalcedon in 451. As scores of bishops and theologians convened at the Church of St. Euphemia, a new orthodox definition of Christology was fashioned, and the Christological deviations of Nestorianism, Eutychianism, and Apollinarianism were formally denounced. The apparent novelty of the Chalcedonian Definition was, in many ways, a synthesis of Cyril’s oeuvre, the Formula of Reunion, and the Tome of Pope Leo, each of which articulated the hypostasis of the Son of God. The resulting definition, therefore, “moved carefully back and forth between the unity of the person and the duality of the natures,” notes Malcolm B. Yarnell III, “providing nuanced statements respecting the continuing yet unmixed relationship of Christ’s natures.”6 “The Chalcedonian Definition,” Boersma concurs, “is a clear amalgamation of Alexandrian, Antiochian, and Western Christologies.”7 As a result, the Chalcedonian Council defined Jesus’s identity as “one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation,”8 a definition which not only coheres with the biblical revelation of the Christ of God but also communicates God’s eternal resolve to redeem his church.

Cyril’s Christological Legacy

Critical to the Chalcedonian synod was the articulation of the flawless congruity of Jesus’s divine and human natures. In contradistinction to the Nestorian and Apollinarian Christologies present, each of which severed the natures of Christ into ambiguous complexes, the orthodox delegates at Chalcedon endeavored to demonstrate how the Son of God was “inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably” consubstantial with both God and Man.9 In so doing, the council confessed its accord with the Alexandrian stream of Christology, much to the chagrin of the Antiochene attendees. This definition, however, was by no means crafted to appease certain delegates. The years leading up to the conference at Chalcedon witnessed an assortment of scholarship on the doctrine of Christ that would weigh heavily on the synod’s eventual declaration, not the least of which was the Tome of Pope Leo I, which was an epistle addressed to Flavian, the Archbishop of Constantinople, in the aftermath of the “Robber Synod” in 449. Leo’s Tome remains a vivid specimen of patristic theology, throughout which conspicuous traces of Chalcedonian vocabulary can be found. For instance, Pope Leo, who is often referred to as Leo the Great, definitively attests to the Lord Jesus Christ:

Who is Very God, is also very Man: and there is no illusion in this union, while the lowliness of man and the loftiness of Godhead meet together . . . And as the Word does not withdraw from equality with the Father in glory, so the flesh does not abandon the nature of our kind. For, as we must often be saying, He is one and the same, truly Son of God, and truly Son of Man.10

Similarly, Cyril’s tomes repudiating his rival Nestorius contain commensurate foretastes of the synod’s eventual Definition. Cyril’s epistolary refutation of Nestorius sees the bishop of Alexandria unambiguously affirm the congruent albeit unconfused natures of the person of the Son:

The God-inspired Scripture says that the Word out of God the Father was made Flesh, i.e., was without confusion and Personally united to flesh . . . since His aim was to assure all that He hath become truly Man, He took hold of the seed of Abraham, and the blessed Virgin being the mean to this same end, He took part like us in blood and flesh; for so and no otherwise could He become God with us.11

Even still, Cyril’s greatest contribution to the posthumous conference was his Commentary on the Gospel According to S. John, which is evident from the Chalcedonian parlance that the Son of God was “consubstantial with the Father according to the Godhead, and consubstantial with us according to the Manhood.”12

In Cyril’s comments on the first chapter of John’s Gospel, he explains the orthodox position of the Son’s co-equality with the Father by emphasizing the consubstantial grammar apparent within the biblical text. Cyril’s work underscores the apostle’s profound Christological prologue, in which the Word is shown to not only subsist in intimate communion with the divine but also to possess intrinsic divinity. “Consubstantial is the Son with the Father,” the Alexandrian bishop asserts, “and the Father with the Son, wherefore They arrive at an unchangeable Likeness, so that the Father is seen in the Son, the Son in the Father, and Each flashes forth in the Other.”13 There is no confusion within the congruence of the Word with the Father. They exist unalloyed even as they remain indivisible and coessential. “Equal therefore and not lesser,” Cyril continues, “is He Who hath the Prerogatives of Essence in common with the Father.”14 Cyril’s accentuation of the Son’s co-equality with the Father is freighted with the concomitant claim of co-eternality. John’s definitive, “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1), necessarily invokes Genesis 1:1 to show a theological coherence between the world’s Creator and its Redeemer. “If there was no time when the Father was without Word and Wisdom and Express Image and Radiance,” Cyril attests, alluding to Hebrews 1:3, “needs it to confess too that the Son Who is all these to the Everlasting Father, is Everlasting.”15

The Son’s everlasting congruence with divinity, however, does not eclipse his consubstantial humanity. Leading up to and following the Nicene synod, the Christological hubbub revolved around the spiritual mechanics of the Word becoming flesh (John 1:14). Humanity’s propensity for change and the Godhead’s unchangeable nature appear to be irreconcilable, inciting theologians to fill the void of explanation by offering their own. The result was an ecclesiological market that was flooded with solutions for apprehending the incarnation, many of which fell far short of the biblical vision of the Son’s assumption of flesh and blood. At Chalcedon, delegates devised a Christological formula that preserved the congruity of the Son’s divine and human natures, dismissing the errors of Nestorianism and other extreme forms of Antiochene Christology that compartmentalized the identity of the Son of God into the deity of Christ and the humanity of Jesus.

The enfleshed Word, therefore, is recognized as one person with two natures, each of which exists “inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably” with the other.16 Insofar as these natures are either partitioned or obscured, the one over the other, the person of the Son becomes a mere assemblage of human and divine components without any conclusive identity. Consequently, Cyril’s apparent stubbornness to concede the title Theotokos for Mary is not only tenable but reasonable for the defense of the orthodox Christian faith since it designates the means by which the eternal Word was contracted to the span of a human body. “There is none other God save He,” Cyril observes, “uniting to the Word that which He bears about Him, as His very own, that is the temple of the Virgin: for He is One Christ of Both.”17

Without devolving into extremes, Cyril’s exegesis of John’s Gospel bears the marks of Alexandrian Christology while also foreshadowing the forthcoming Christological definition of Chalcedon that would become a mainstay for countless generations of believers. Cyril leaves the mystery of the incarnation undisturbed, even as he articulates its necessity. Indispensable to the reconciliatory work of the Son of God is the simultaneity of his divine and human natures, which not only allows him to represent human beings but to do so perfectly. “If all that the Father hath,” Cyril explains, “are wholly the Son’s, and the Father hath Perfection, Perfect will be the Son too, Who hath the properties and excellencies of the Father.”18 Accordingly, Cyril’s place within historical theology endures not only as a forerunner to the Chalcedonian Definition but also as a faithful forebear for the church.

Chalcedon’s Indelible Impact

Despite how remote the Chalcedonian narrative may seem, the creed it birthed is teeming with Christological ramifications that remain unendingly germane. Far from being any abstract chapter of patristic controversy, the disputes precipitating the eventual conference are still echoing in the halls of the churches of modernity, compelling contemporary theologians to conscientiously “contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3). Even as some of the foremost voices of the early church wrangled over the doctrinal and theological particularities related to the person of the Son of God, much more than mere Christological precision hung in the balance. “The religious experiences and the worship of the people were at stake,” Boersma comments.19 The apparent esoteric bickering over the dynamics of Christ’s two natures is an indispensable component of orthodox Christianity, shaping the church’s grasp of its quintessential confession and mystery of redemption (1 Tim. 3:16). Accordingly, as the church fulfills its commission to witness to the ineradicable work of reconciliation in the immutable person of Jesus, she unwittingly imitates Cyril and the other Chalcedonian bishops in the preservation of humanity’s only hope of salvation.

Justin S. Holcomb, Know the Creeds and Councils, KNOW Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014), 54.

Cyril of Alexandria, Five Tomes Against Nestorius (Oxford: James Parker & Co., 1881), 13.

Nestorius of Constantinople, The Bazaar of Heracleides, edited and translated by G. R. Driver and Leonard Hodgson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925), 132.

Steven A. McKinion, “Jesus Christ,” Historical Theology for the Church, edited by Jason G. Duesing and Nathan A. Finn (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2021), 32.

Hans Boersma, “The Chalcedonian Definition: Its Soteriological Implications,” WTJ 54.1 (Spring 1992): 57.

Malcolm B. Yarnell III, “Christology in Chalcedon: Creed and Contextualization,” Southeastern Theological Review 11.2 (Fall 2020): 16.

Boersma, 62.

Holcomb, 56.

William Andrew Hammond, The Definitions of Faith, and Canons of Discipline, of the Six Œcumenical Councils (Oxford: John Henry Parker, 1843), 82.

Leo the Great, Select Sermons on the Incarnation; with His Twenty-Eighth Epistle, Called the “Tome,” translated by William Bright (London: J. Masters & Co., 1886), 115.

Cyril, Five Tomes, 8–9.

Hammond, 82.

Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on the Gospel According to S. John, Vol. 1 (Oxford: James Parker & Co., 1874), 17.

Cyril, John, 31.

Cyril, John, 12–13.

Hammond, 82.

Cyril, John, 110.

Cyril, John, 31.

Boersma, 50.

Good word! Thanks for sharing.