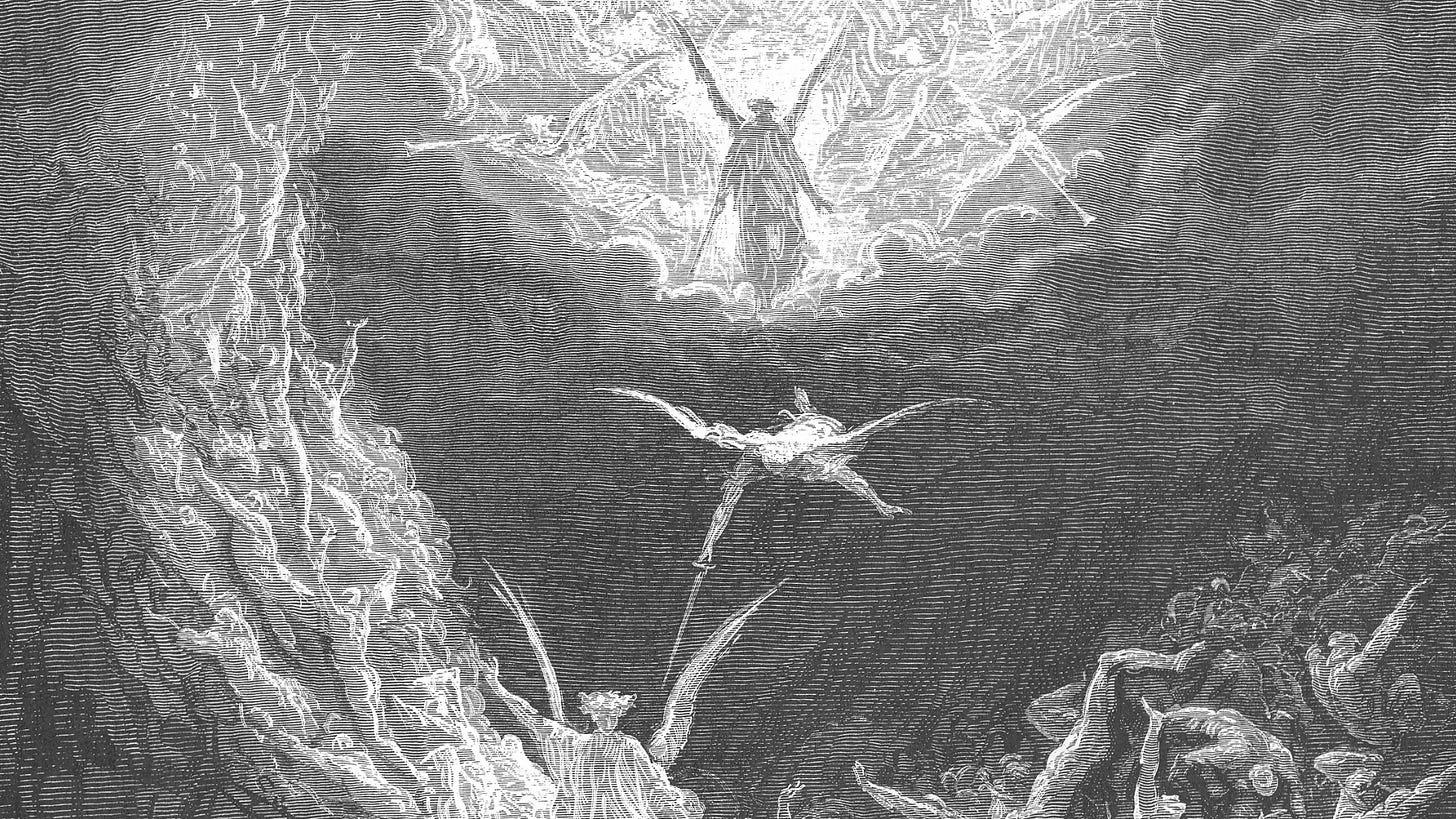

Rediscovering the Eschaton.

A few thoughts on cultivating a balanced eschatological understanding in the church.

Conspicuously absent from many of the theological contributions and formulations that emerged out of the Protestant Reformation was any robust doctrine of eschatology. While the bulk of the reformers’ efforts were expended grappling with the papacy over the biblical view of justification, and rightfully so, there was minimal exegetical work done to explain the end of all things scripturally. In fact, the foundational documents for Lutheran and Anglican churches in the sixteenth century, the Augsburg Confession and the Thirty-Nine Articles, respectively, only make passing mentions of the second coming and the accompanying judgment of Christ. Article XVII of the Augsburg Confession refers to “the Consummation of the World” that will occur at Jesus’s second advent, but is itself mostly a polemic against eschatological extremism rather than an exegetical clarification of Protestant eschatology.

By the nineteenth century, the overall dearth of eschatological scholarship had shifted into a surplus of apocalyptic exegesis, which only escalated as the world reeled in the aftermath of two global conflicts. The prospect of world war brought with it a theological vulnerability that began to be placated by a burgeoning interest in prophetic and apocalyptic biblical exposition, which developed into a veritable kaleidoscope of eschatological interpretation. In many ways, the superfluity of eschatological interest has resulted in more, not less, confusion concerning the biblical particulars of the end times. As Malcolm B. Yarnell III explains, this has led to the emergence of what he refers to as either “eschatomania” or “eschatophobia,” wherein the church’s relationship to the doctrine of eschatology is either overindulgent or impoverished.1

To that end, there is a pressing need for churches to impart a biblically healthy understanding of eschatology to their disciples, one that is neither obsessively fearful nor preoccupied with eschatological investigation. After all, as Christ revealed to his followers, “no one knows” the times or the seasons of his parousia (Mark 13:32–33; Acts 1:6–8). This, to be sure, was not to incite hand-wringing or pensive brooding over the specifics of his return; rather, it was to instill in his church a hearty urgency that would stoke their evangelistic zeal. The apostle Peter makes this apparent in his first epistle when he refers to the imminence of the Lord’s return as an incentive to earnestly show one another love and hospitality (1 Pet. 4:7–10). The benefit of eschatological instruction, therefore, is best demonstrated in a church’s evangelistic enthusiasm and hearty welcome.

Malcolm B. Yarnell III, “Eschatology,” Historical Theology for the Church, edited by Jason G. Duesing and Nathan A. Finn (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2021), 384.

I agree completely with your views on Luther and end times. FWIW - I think one of the reasons that there may seem to be a vacancy of eschatological teaching in Reformed theology is that there isn't just one perspective. Some believe in a version of postmillennialism, others in amillennialism, and some hold to a type of premillennialism that's not as extreme as early church views or modern dispensationalism. There were even different views among the Westminster Assembly members. I find that early reformed theologians like Calvin, Edwards, Warfield and Bavinck addressed eschatology more fully than Luther, but didn't all share the same views. My position as a reformed believer - it's above my pay grade. I'll just keep watching for Christ until I see Him, coming again to earth or in heaven.

Im currently post mill, and agree with this. Just picked up a great book from American vision that compares all the major views, it’s very helpful