Grace for When the Sermon’s Over

Why vulnerability matters when you’re in the pulpit.

As a pastor, or a “man of the cloth” as we are known in some corners of Christendom, there’s a certain stigma about opening up too much when you’re in the pulpit, one that every pastor feels without ever really talking about it. There’s a line of vulnerability preachers aren’t supposed to cross, or else they risk defaulting on their position. After all, if you’re too vulnerable with your faults and failures, who’d wanna listen to you pontificate about the excellencies of Christian doctrine, am I right? But since this isn’t a pulpit, it’s Substack, I’m going to dare to show you my cards.

Easily, the weakest and most vulnerable moment of my week is always the same. It starts the nanosecond I exit the pulpit once I’m done with my Sunday morning sermon and bleeds into the ensuing seconds or even hours afterwards. That’s when a deluge of self-imposed judgment rushes over me; that’s when I think of all the things I could have said better or made clearer. That’s when all the words I didn’t say, but should have, and all the words I did say, but shouldn’t have, become so glaringly and painfully obvious. It’s in those eternal seconds that I feel like a failure in the most pointed way imaginable. “Surely, someone’s more fit for this office than me!”

A mess of conflicting emotions converges all at once. I’m reminded of the promise that God’s words never return void, but then I wonder if that’s still true when it seems as though you’re speaking into the void. I hasten to put on a smile and shake hands with all those in attendance as they depart the sanctuary, calculating all the ways I could’ve served them better. Or maybe how someone else could’ve served them better. I attempt to make small talk and act like I don’t need anyone’s, “Good sermon, Pastor Brad,” even though I know I do. I try to pretend that I don’t, but there’s a part of me that lives for those comments. I loathe that part of myself. After all, what good is that approval other than to slake the appetite of my own ego?

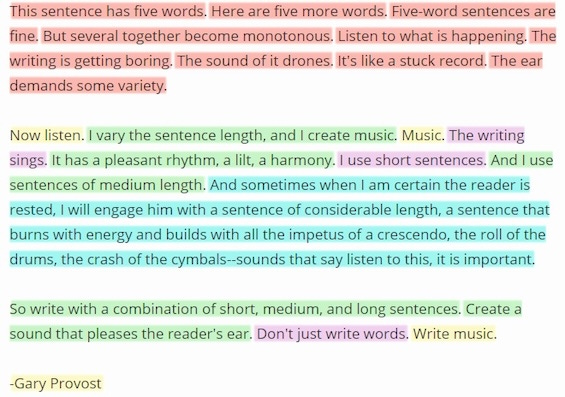

Part of my sermon to myself when my sermon is over is reminding myself that my identity and status as a child of God aren’t contingent on whether or not my sermon was a success or a disaster, which, to be sure, is very hard to believe at times. As one who loves words1 and gets a real joy out of putting them together in sentences to convey a range of emotions and/or reactions, I resonate with what Paul tells the church at Corinth in his first letter to them. I get the allure of “lofty speech” and “plausible words of wisdom” (1 Cor. 2:1, 4). When I wrote my first book, one of the most frequent comments I received was that I used a lot of big words. To be honest, I’m still very self-conscious of that.

I don’t use big words for the mere sake of brandishing my vocabulary, or to show you how well I can navigate a Thesaurus. That’s just how I talk. There’s something beguiling about putting words together in unexpected ways — ways that compel the reader not to reconsider what they just read, but to reconsider what they used to think. But what good would that do my church? Who’d benefit the most if all I did was get up and string a bunch of fancy-sounding words together, and call that my “sermon”? It might sound good, but it wouldn’t serve anyone’s soul.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I think sermons should be endowed with a certain sense of artistry and creativity, and thoughtfulness, the kind that makes hearing the words of the gospel compelling. I’ve heard the anecdotes regarding Jonathan Edwards’s dull, monotone delivery. I’m not saying we should strive for that. But what I am saying is that a sermon’s power, ultimately, isn’t a consequence of my innovation. What moves sinners and saints to receive the grace that’s so freely given to them in Christ isn’t my charisma or eloquence, nor is it my ability to speak compellingly. It’s the Spirit who indwells those who believe and enables them to discern the Word that’s spiritually discerned.

You see, what I’ve become convinced of is that my effectiveness as a preacher is intimately connected to my death. (Spiritually speaking, of course.) Prior to ambling up onto the platform and positioning myself behind the pulpit, and opening my iPad to deliver my sermon, I have to die to any fleshly voice that craves attention, that yearns for the spotlight, that longs for acclaim. I have to die to any lingering worries about what you might want to hear or not want to hear, or what you might think about me. The preacher in me who longs for renown has to be crucified. After all, what’s the pulpit for?

It’s certainly not a time to show off how eloquent I can be or how trendy I am. As Steve Smith once put it, “Preaching is not a display case for rhetorical ability; it is not a place to show how traditional or trendy we are; it is not a place to fulfill aspirations of glory. The pulpit is a place to die so that others might live.”2 I have to read and re-read that quote often, not to convince myself it’s true, but to let its truth sink down deep. Whatever glory I might find in preaching well pales in comparison to the glory of being crucified in the pulpit so that others might live. “A crucified Savior,” Ray Ortlund, “can be preached in divine power only by crucified preachers.”3

This, I think, is what Paul was getting at in his Corinthian epistles. When he writes that he “decided to know nothing among [them] except Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2), he’s cluing them into a conscious decision he made prior to visiting them with the gospel. This Gamaliel-educated Pharisee, whose prestigious résumé was once his calling card, now understands that all those degrees and statuses are nothing but a pile of rubbish, to put it politely (Phil. 3:8). What did it matter if he could recite the Torah with all the Pharisaical rhetoric that’d make his peers jealous? No, he’d rather become a fool for their sake so that they might become wise unto salvation (1 Cor. 3:18–19). And there’s nothing more foolish than directing everyone’s gaze to a crucified Messiah as the locus of everlasting hope and redemption.

Sammy Rhodes, campus minister for Reformed University Fellowship at the University of South Carolina, once put it like this:

At the cross, Jesus was stripped so that we might be covered. The reason we can be vulnerable is that the God of the universe was first vulnerable for us. Because he has secured our forgiveness — the once-and-for-all taking away of our shame — vulnerability goes from being a life-threatening act to a life-giving one.4

I get that there’s a standard for eldership in the Pauline epistles. But that doesn’t preclude the office from vulnerability, especially since the church’s Yes and Amen accomplished our salvation by embracing the vulnerability of death on a cross. In light of that, I can be honest about my bouts with depression, discouragement, and disappointment, since it’s precisely those who are broken who are healed by grace. I can stare my inadequacies in the face and know that, despite how glaring they are to me, God’s Son isn’t standoffish. I can keep preaching, in spite of my self-doubt and insipid selfishness, because the Word that prevails on souls prevails in spite of me. After all, my calling as a preacher, at least as I understand it, isn’t to embody or even pretend that I have it all together; it’s to gesture to the one who is.

Grace and peace to you, my friends.

Almost as much as I love fonts!

Steven W. Smith, Dying to Preach: Embracing the Cross in the Pulpit (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2009), 27.

Raymond C. Ortlund, Jr., “Power in Preaching: Decide (1 Corinthians 2:1-5) Part 1 of 3,” Themelios 34.1 (2009): 80.

Sammy Rhodes, This Is Awkward: How Life’s Uncomfortable Moments Open the Door to Intimacy and Connection (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2016), 8.

You are a blessing from every side of the pulpit.

I have a wise friend who likes to say, "The most important thing about me is that I am loved by God."

As a former staff member at a very "performance-heavy" church, I have adopted his phrase as something of an anchor, and as a counterpoint to all other alternatives that are very easy for sincere christians to believe. It's easy for us to believe something like, "The most important thing about me is that I serve God," or "the most important thing about me is that I am useful to God," or even (and this is subtle, and reformed theology has helped me understand the danger in this one): "the most important thing about me is that I love God."

I do not "perform" in church these days, but I am still tempted by these thoughts and feelings daily. So I feel ya, Brad. Just know this: "The most important thing about you is that you are loved, and that by God."