A Shelf to Read and a Savior to Cherish

Horatius Bonar on the church’s guiding confession and why the gospel still needs to be simple.

Although I don’t really make them or make a big deal about them, if I were a “New Year’s Resolution” person, my aim for 2026 would be to be more candid with what I’m reading, which, theoretically, would result in more candidness in what I write. I am eager to do just that this next year, and though I’ve tried and failed to be a more disciplined reader over the last several years, alas, I still have nearly a shelf-full of books from various genres that are all in various states of completion. While some have a “to-read list,” I have a “to-read shelf.” A previous resolution of mine was not to read any new books until I had finished the ones I had already started. But that resolution was short-lived, to the point where now I’ve just accepted the fact that I will always have a to-be-finished section in my library, in perpetuity.

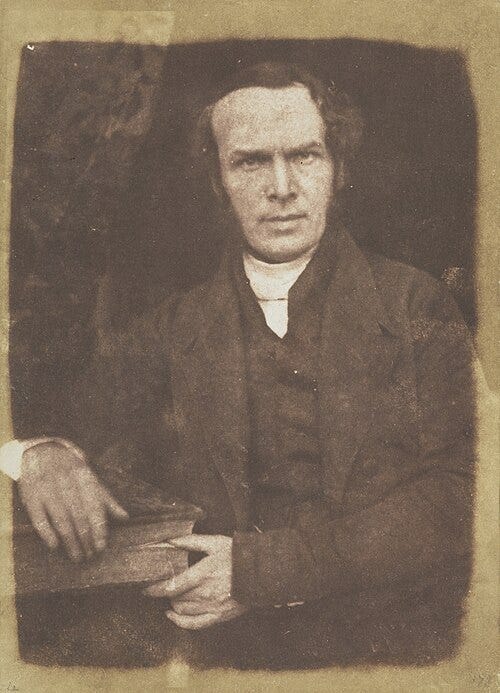

One book I picked up recently (that is, I found for free on Google Books), which I have been keenly focused on finishing, is Horatius Bonar’s The Christ of God. Published in the late 1800s, this treatise comes from one of my favorite Scottish churchmen and theologians. I’ve never been gun-shy about my affinity for Horatius’s writings. I’ve extolled the merits of his oeuvre countless times, especially his truly formative The Story of Grace, but I can’t get over how well he articulates “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3) in nearly everything he published. Renowned for his hymns, Horatius’s “evangelical” verve is almost unrivaled, in my eyes, by which I mean the euangelion was almost always bursting at the seams with every sentence. The freeness and the fullness of God’s grace for sinners seem always just around the corner, put into such poignant and provocative expressions, you’d think he was one of those shock-jock authors or preachers, just yearning for a reaction.

But Horatius’s ambition never feels thin or tawdry. Rather, his writing feels like a project where, via a kaleidoscope of approaches, his singular aim is to make much of the gospel that actually saves actual sinners, among whom he himself knows he belongs. You never get the sense, or at least I don’t, that Horatius was talking down to whomever he had in mind while writing, whether that be his parishioners in Kelso or his neighbors in Edinburgh. He wrote with a knack for understanding what makes God’s good news so endlessly compelling and dripping with grace — namely, its announcement that God’s own Son has accomplished everything necessary for ghastly sinners like you and me to be cleansed and forgiven. “The whole completeness of that which we call salvation,” he writes in The Christ of God, “is to be found in Him, without stint, or lack, or grudging.”1 We who are uttermost sinners are desperate for an uttermost Savior, which is precisely who Christ is for us.

With that said, The Christ of God is quickly crawling up my list of favorite works Horatius Bonar ever wrote. In many ways, it’s an extended treatment of Peter’s confession in the Synoptics that Jesus of Nazareth is “the Christ” (Matt. 16:13–16; Mark 8:27–29; Luke 9:18–20). And while he devotes an entire chapter to that scene from the Gospels, the entire treatise feels very much downstream from that seminal moment. He takes his time, treating this subject with the necessary care and consideration it deserves. You’ll find his typical earnestly devotional polish evident in each of the ten chapters, even in the longest of the bunch, Chapter 5, “Thou Art the Christ, What Then?,” where Horace (that’s what his friends apparently called him) ponders what’s involved when the Lord’s impetuous disciple confesses that his beloved Rabbi is none other than the Christ of God.

From the promised Seed to the true Prophet to the conquering King to the Lamb that was slain, in Christ Jesus, the world witnesses “God Himself, coming to sinners on an errand of grace.”2 He was no mere mortal, no mere teacher, who had been uniquely or uncannily imbued with divine wisdom, insight, or forethought. Jesus is no superhuman, and the Gospels aren’t his origin story. Rather, in Jesus, as Horatius puts it, “God Himself has taken the side of man; yea, has become man, that He may accomplish man’s deliverance.”3 It’s a mystery that defies comprehension, one that can only be held and confessed in Chalcedonian tension. In Jesus, we are shown he who is both Lord and Christ, true God and true Man, “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.”4

He it is that brings about our full and free redemption, which, in its fullest and truest sense, “means the actual accomplishment of the thing contemplated, the full deliverance of the objects for whom the ransom was paid down.”5 As has been said before, when the Crucified One uttered those marvelous words, “It is finished,” he meant it. He wasn’t misleading anyone or speaking facetiously; he was putting his declarative signature on the “actual accomplishment” of humanity’s reconciliation to the Father. And we know that this is the case because of who it is that says it. The Eternal Logos. The Yes and Amen. The Christ of God. Embodied for us, he is crucified and risen for us, too. And as we confess and believe that Jesus is the Christ, we are delivered, redeemed, and made whole (Rom. 10:9–10). Indeed, what makes the Christian confession so alarming is its simplicity. It sounds too good to be true, but it is true. Here’s how Horatius Bonar puts it:

In receiving this divine testimony, we become connected with the redemption and the Redeemer. Not by waiting, or working, or buying, or deserving, do we get this whole redemption and this whole Redeemer, but simply by believing . . . do we say it is too simple to be true? Surely we cannot be delivered and justified by simply believing! Well, go and dispute the matter with God, and ask Him His reasons for putting it so simply. Persuade Him to mystify His language, and alter His terms. But, till you have succeeded in procuring from Him the changes which you think would make it a better and safer gospel, it would be well for you to take it as it is. You are not likely to improve it; and to render it more complex in its terms, would only place it beyond the reach of sinners who, sensible of total impotence and unworthiness, find it in its simplicity the only good news suitable to their case.6

I think the point is that humanity’s impulse will always tend toward adding complexity where it’s not needed or warranted. This is certainly the case with the gospel of God, which reveals the method and means by which humanity is rescued from eternal damnation through the person and work of God’s Son, the Christ. And yet, it is this same gospel that has been tweaked and reconfigured through the ages to the point where how simple it is and how free it is are elements that are far too often left to fall by the wayside. In their stead, the church adds performative measures of discipline, virtue, and piety to ensure that its adherents are on the up-and-up. But part of me believes that through all the disciple-making shenanigans by which the church sometimes becomes weighed down, it has forgotten that its target audience is sinners.

I am by no means implying that discipline, virtue, and piety are unimportant. Of course not. No sensible theologian would ever make such a claim. But I am saying that the church and its leaders are often guilty of putting the cart before the horse when those ends are made “the end” of the pursuit of God. The gospel, in a sense, becomes a means to an end instead of the world in which sinner-saints are meant to live and move and find their being, their purpose, their hope. Instead of merely a gateway to spiritual formation, the gospel is the air in which we are formed by the Spirit, whose ministry to us, the church, always gestures towards the actual accomplishments of the Son, the Christ of God. The life of faith, you see, really is all about holding fast to “the confession of our hope without wavering,” knowing that “he who promised is faithful” (Heb. 10:23). That confession, of course, is that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ of God, crucified and risen, for you.

Grace and peace to you, my friends.

Horatius Bonar, The Christ of God (London: James Nisbet & Co., 1874), 105.

Bonar, 67.

Bonar, 73.

Justin S. Holcomb, Know the Creeds and Councils, KNOW Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014), 56.

Bonar, 102.

Bonar, 103–4.

Thank you for sharing this devotional it beautifully reminds us that while books wisdom and good teaching are valuable the greatest treasure is Jesus Himself and all Scripture points us to Him the Word of God tells us that Christ is more precious than gold and sweeter than honey and in His presence there is fullness of joy Psalm 19:10 Psalm 16:11 wisdom calls us to buy truth and understanding Proverbs 23:23 and the New Testament reveals that all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge are hidden in Christ Colossians 2:3 a shelf full of books is a blessing but a heart filled with Christ is life itself as Scripture urges us to let the word of Christ dwell in us richly Colossians 3:16 because Jesus alone is the way the truth and the life John 14:6 when we cherish the Savior above all every book sermon and study draws us closer to Him and helps us press on toward the goal of knowing Christ Philippians 3:13–14 may our hearts always hold fast to this hope without wavering knowing He who promised is faithful Hebrews 10:23