A Legacy of Faith in Print

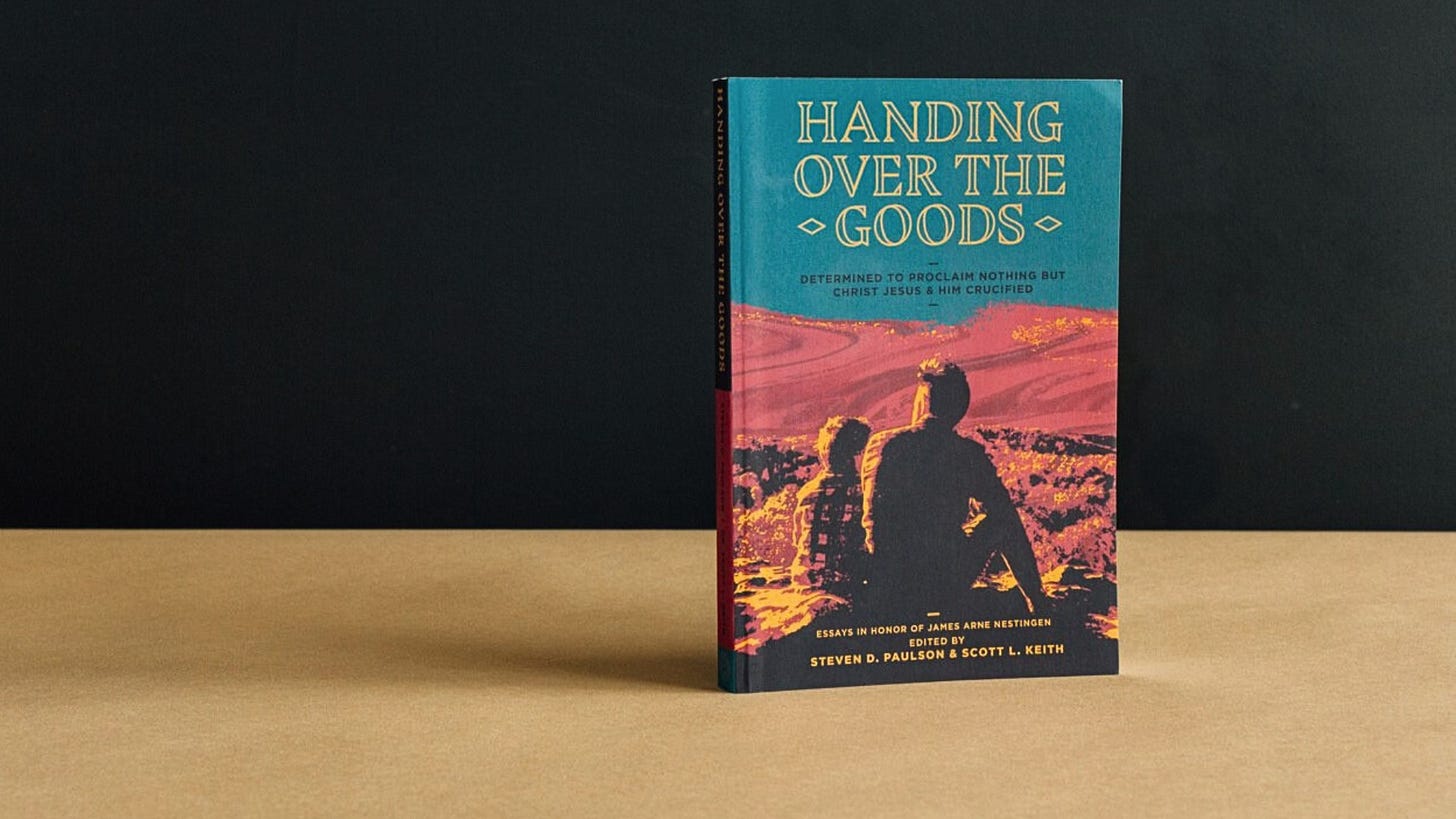

Reviewing Steven D. Paulson and Scott L. Keith’s “Handing Over the Goods.”

James A. Nestingen was ushered into eternity on New Year’s Eve in 2022. His theological legacy speaks for itself, having served as a pastor and/or professor for various Lutheran institutions throughout his lifetime, most notably at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. Students of the Word are still reaping the benefits of those he tutored, as his lectures reached countless lives with the truth of God’s Word of Promise as made manifest in the person of Jesus. A few years prior to his passing, fellow professors and theologians Steven D. Paulson and Scott L. Keith assembled a plethora of scholars and students, many of whom sat under his instruction, to compose essays in Nestingen’s honor, commemorating his legacy as a lecturer, author, and mentor. The result is Handing Over the Goods: Determined to Proclaim Nothing But Christ Jesus & Him Crucified: Essays in Honor of James Nestingen, a volume whose resonance has only expanded in the time since its namesake’s passing.

The work itself is a compendium of essays from a variety of authors covering a smorgasbord of theological subjects. Featuring essays from Robert Kolb, Ken Sundet Jones, Mark Mattes, Hans Wiersma, and the late Rod Rosenbladt, Handing Over the Goods manages to combine an embarrassment of theological riches into a single volume of writings that is poised to afford clergy and laity alike ample opportunity to deepen their understanding of the gospel and the theological convictions that emerge in light of it. After a brief introductory note penned by the editors themselves, Paulson and Keith, a string of loosely connected essays ensues. From examining the Lutheran view on the sacrament of baptism to the effective end of the law for justification, to the modern resonance of Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation to the essence of sanctification, there are few ecclesiological stones that are left unturned.

Although I confess a different conviction concerning the function or mode of baptism, it was considerably helpful to reckon with the essays on that ordinance by Mark Tranvik and Thomas Aadland. Differences aside, the significance of the baptismal event is best portrayed in the language of death and resurrection (Rom. 6:3–6). Another notable essay is Ken Sundet Jones’s contribution, “Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation: A Little Course on Preaching,” in which Luther’s theses from 1518 are reviewed through the paradigm of the preaching event. Just as the German reformer asserted that one’s knowledge of God cannot be divorced from the cross, so, too, are preachers to understand their role as cruciform messengers. “If preachers,” Ken writes, “want people to become the strongest witnesses of the gospel and the ones who have come to know what’s what, then people suffering under the cross must be the primary target of their preaching.”1

Additionally, Robert Kolb’s essay entitled “Luther’s Transformation of Scholastic Terms” is incredibly impactful in aiding one’s perception of the events that precipitated the Reformation. As Kolb maintains, the lynchpin of the Reformation movement was a profound realization that the righteousness of God as referred to in the New Testament is none other than the righteousness of Christ that is gifted to sinners by grace through faith in his death and resurrection. Accordingly, followers of Christ are imbued with assurance since, as Kolb says, the “integrity of the forgiven sinner and the believer’s identity as a child of God rested on the recreative Word of God that pronounced God’s chosen people righteous on the basis of Christ’s death and resurrection.”2 Likewise, seeing Rod Rosenbladt’s much-acclaimed sermon, “The Gospel for Those Broken by the Church,” in print is a delight.

Perhaps the only critique of this volume would be its need for better organization of its essays, by which I mean that the book could have benefited if the entries were organized by their overall themes. Rather than moving from a discussion of the law to a discussion on baptism only to return to the topic of the law, readers might have been aided by grouping these essays into broader categories, such as Law, Church, Baptism, etc. What is evident, though, is that Nestingen’s theological contemporaries and descendants have adopted his passion for the grace and truth of Christ for Christ’s church. One can only hope that more of that passion for Christ’s passion can be “handed over” in subsequent generations.

Grace and peace.

Ken Sundet Jones, “Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation: A Little Course on Preaching,” Handing Over the Goods: Determined to Proclaim Nothing But Christ Jesus & Him Crucified: Essays in Honor of James Nestingen, edited by Steven D. Paulson and Scott L. Keith (Irvine, CA: 1517 Publishing, 2018), 98.

Robert Kolb, “Luther’s Transformation of Scholastic Terms,” Handing Over the Goods, 38.

Thanks for this review. I would like to read this Festschrift some day. I am sorry that I will never be able to meet Dr. Nestigen in person. While writing my forthcoming novels, I benefitted from listening to an episode of Thinking Fellows where he discussed Luther's "Bondage of the Will." I think about his principles now when I am attempting to comfort Christian friends who are struggling for whatever reason. I assure them that their sins are forgiven for Christ's sake.