Don’t quit, preacher.

Hang on knowing that there’s a stronger One who is hanging on to you.

Perhaps unbeknownst to most, when preachers exit the pulpit there is a flurry of thoughts that race to have first place. There are feelings of accomplishment and failure and disappointment and relief and weakness — speaking from experience, it’s a veritable cocktail of emotion. Although I may not be able to prove this scientifically, I’d say that a pastor is most susceptible to thoughts of “quitting” when he’s stepping off the platform at the close of his sermon. There has been no shortage of instances where I felt that most palpably.

“You should just quit because that was awful,” says the voice in my head.

“You forgot to say such-and-such and make thus-and-thus application.”

“You let your people down!”

“You shouldn’t have said that.”

“You should have said this.”

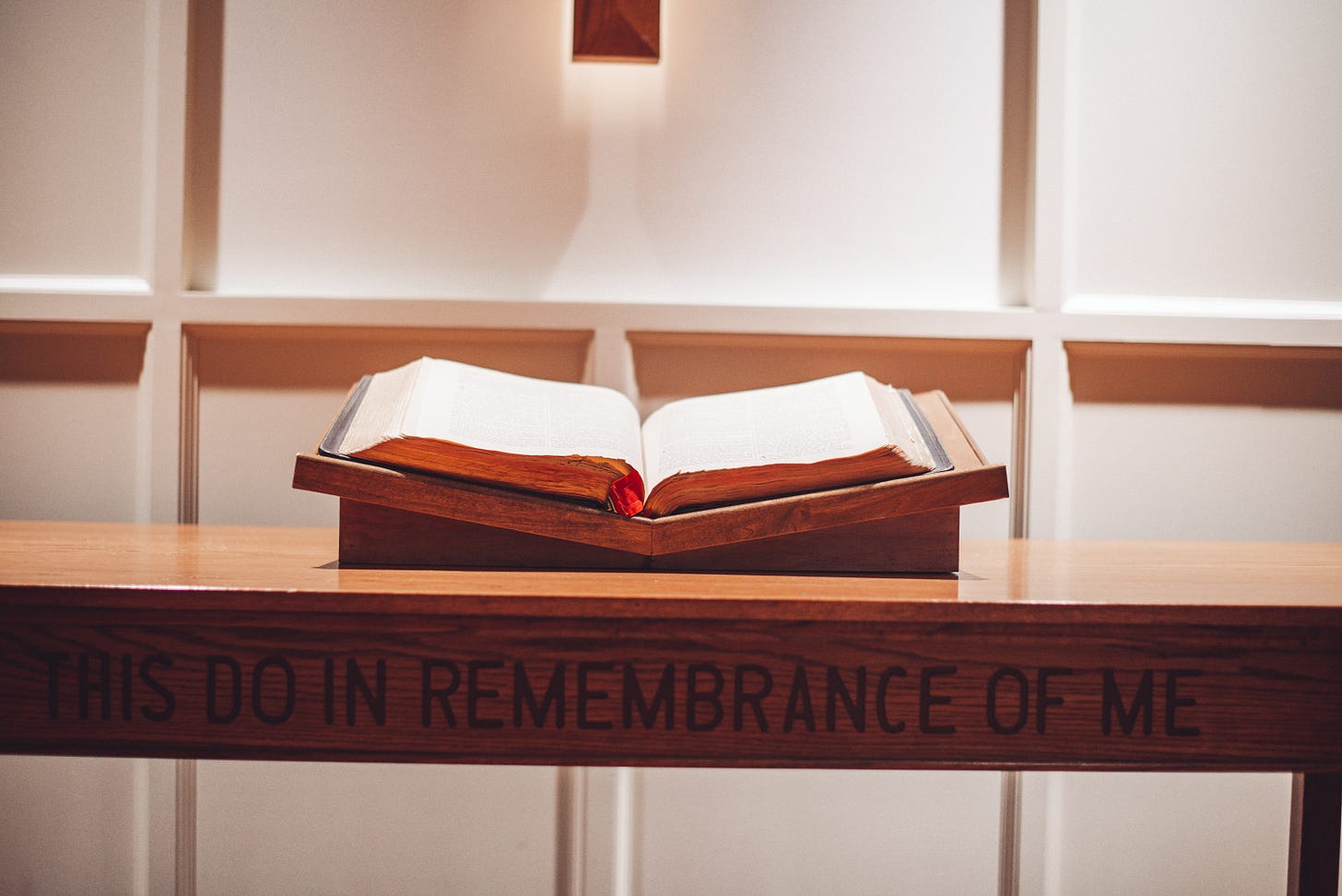

I’d be lying if I said I’ve never had those lines go through my head after a Sunday morning sermon. The busyness of shaking hands with church family and small-talking with visitors as the service wraps up sometimes delays those thoughts from taking over — but their eventual coup is inevitable. When those particular Sundays happen, I have to force myself to deliberately ponder and consider the fact that my identity isn’t tethered to how well my sermon went. God’s Word is powerful and true and “sharper than any two-edged sword” — and that has nothing to do with me. I’m grateful, therefore, to have stumbled across these words from Rev. Alexander Whyte in a 1908 letter to a brother-pastor who sought his counsel. These are, indeed, rousing words for every minister of the gospel:

Never think of giving up preaching! The angels around the throne envy you [for] your great work. You “scarcely know how or what to preach.” Look into your own sinful heart, and back into your sinful life, and around on the world full of sin and misery and open your New Testament, and make application of Christ to yourself and your people; and, like Goodwin, you will preach more freshly and more powerfully every day till you are eighty . . .

Don’t hunger for books. Get a few of the very best, such as you already have, and read them and your own heart continually: and no fear of your preaching. For generations, Rutherford has inspired the best preaching in Scotland. Behmen “had no books, but he had himself,” and, though you had the whole Bodleian Library, and did not know yourself, you would not preach a sermon worth hearing.

Go on and grow in grace and power as a Gospel preacher. (Barbour, 307–8)

As a pastor who’s still in the beginning stages of his ministry, I find immense comfort in these words. Oftentimes, my own internal expectations can drown out the joy and victory of the pastorate. Sometimes the ways I’ve failed out-volume the ways Jesus succeeds for me. But this, I think, is merely evident that my nature is incessantly incurvatus in se — turned in on itself. I’m desperate to have my gaze reoriented off myself and onto my God. Fortunately, the gospel’s good for preachers, too.

I’m doggedly gospel-centered (as rote as that phraseology has become lately) precisely because I’m just as desperate for the gospel as the next guy or gal. I need daily, fresh reminders of Jesus’s “grace upon grace” because I’m prone to forget what that means and what that entails and that it’s true for me. So even when there are voices in my head that taunt me with the thought of “giving up preaching,” a better Word comes to my ear. It is the Word of God’s grace, which reminds I am who I am, and where I am, because of Christ alone (1 Cor. 15:9–10).

Brother-preacher, never think of giving up preaching. Hang on knowing that there’s a stronger One who is hanging on to you.

Soli Deo Gloria. Amen.

Works cited:

G. F. Barbour, The Life of Alexander Whyte (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923).